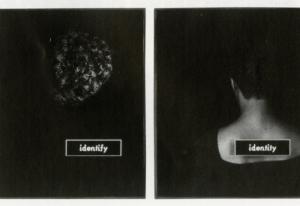

Act Like You’re Fine: A Study on Obsession, Vacant Gallery, Tokyo, 2011

Slava Mogutin is a New York-based Russian-American multimedia artist, filmmaker and writer exiled from Russia for his outspoken writings and activism. Mogutin’s work is informed by his bicultural literary and dissident background, encompassing the themes of displacement and identity; transgression and disfiguration of masculinity and gender crossover; urban youth subcultures and adolescent sexuality; the clash of social norms and individual desires; the tension between attachment and disaffection, hate and love.

Born Yaroslav Yurievich Mogutin (Ярослав Юрьевич Могутин) in the industrial city of Kemerovo, Siberia, he left his family and moved to Moscow at age 14. A third-generation writer and a self-taught journalist, he soon began working as a reporter and editor for the first independent Russian newspapers, publishers, and radio stations, such as Echo of Moscow, The Moscow Times, The Moscow Guardian, Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Stolitsa, and Novy Vzglyad. He was hailed as one of the foremost voices of the post-Perestroika new journalism and the only openly gay personality in the Russian media.

By the age of 21, Mogutin had gained both critical acclaim and official condemnation and became the target of two highly publicized criminal cases, carrying a potential prison sentence of up to seven years. He was charged with “open and deliberate contempt for generally accepted moral norms,” “malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence,” “inflaming social, national, and religious division,” “propaganda of brutal violence, psychic pathology, and sexual perversions.” In 1994, Mogutin attempted to register officially the first same-sex marriage in Russia with his then-partner, American artist Robert Filippini. The attempt made headlines around the world, but only further fueled his persecution by the authorities.

Forced to flee his country in 1995, Mogutin became the first Russian to be granted political asylum in the US on the grounds of homophobic persecution. His case for asylum was supported by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, Committee to Protect Journalists, and PEN American Center, setting the precedent for many other gay and lesbian refugees from the former USSR.

Upon his arrival in New York, Mogutin shifted his focus to visual art and started using his nickname Slava—”glory” or “fame” in Russian—as his artist name. His photography and multimedia work have been exhibited internationally, including MoMA PS1 and Museum of Arts and Design in New York; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco; The Pacific Design Center in LA; Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston; Moscow Museum of Modern Art; Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney; Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam; Overgaden Institute of Contemporary Art in Copenhagen; Estonian KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC) in Spain; The Haifa Museum of Art in Israel, and, most recently, Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art (iMOCA).

Mogutin is the author of two critically acclaimed monographs of photography published in the US, Lost Boys and NYC Go-Go (powerHouse Books, Brooklyn, 2006 and 2008), and seven books of writings in Russian. In 2000, he was awarded the Andrei Bely Prize, one of the most prestigious literary awards in Russia. His poetry, fiction, essays, and interviews have appeared in numerous publications and anthologies in ten languages. He has translated into Russian selected writings of Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Dennis Cooper.

Mogutin’s work has been featured in a wide range of publications, including Flash Art, Modern Painters, i-D, Dazed & Confused, Visionaire, L’Uomo Vogue, Stern, Libération, and The New York Times. He is a regular contributor to The Calvert Journal, Whitewall, Vice, Flaunt, The Stranger, and The Huffington Post. He has lectured extensively throughout the US, including Columbia University, Yale, Harvard, Harriman Institute, Grinnell College, Stevens Institute of Technology, Middlebury College, Parsons The New School for Design, and School of Visual Arts. As an actor he appeared in Bruce LaBruce’s agitprop porn film Skin Flick (1999) and Laura Colella’s independent feature Stay Until Tomorrow (2004).

In 2004, together with his partner, American artist Brian Kenny, Mogutin co-founded SUPERM, a collaborative art team responsible for site-specific gallery and museum shows in the US, Canada, Russia, Israel, and across Europe. In 2011, Mogutin was naturalized as a US citizen and legally changed his name to Slava. He is a vocal critic of President Vladimir Putin and his recent anti-gay policies. In March 2014, Mogutin released his first collection of writings in English, Food Chain, published by the Brooklyn-based ITNA Press. He’s currently at work on his third monograph of photography based on his studio portraiture and a book of essays and interviews, covering over 20 years of his journalistic work.

Resource : http://slavamogutin.com